Nicolas de Gunzburg - Muses and the Beau Monde

- Lilium

- Oct 26, 2022

- 6 min read

Nicolas Louis Alexandre de Gunzburg, born 12 December 1904, also known as Baron Nicolas de Gunzburg, was a French-born magazine editor and socialite. He became an editor at several American publications, including Town & Country, Vogue, and Harper's Bazaar. He was named on the International Best Dressed List Hall of Fame in 1971.

Baron Nicolas "Niki" de Gunzburg was born in Paris, France, a scion of a wealthy and influential Russian-Jewish family, whose fortune had been made in banking and oil. The Günzburgs, as they were originally known, were ennobled during the 1870s by Louis III, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine. When family members began spending a great deal of time in France later in the century, the umlaut was dropped and the particle "de" adopted. Their Hessian title was made hereditary in 1874 by Czar Alexander II of Russia.

His father was Baron Gabriel Jacob "Jacques" de Gunzburg, a nephew of the Russian philanthropist Baron Horace Günzburg. His Brazilian-born mother, Enriqueta "Quêta" de Laska, was of Polish and Portuguese descent, a daughter of Doña Joaquina Maria Marqués de Lonza Lisboa. Raised primarily in England, where his father worked for the bankers Hirsch & Co. and served as a director of the Ritz Hotels Development Corporation, Gunzburg spent his later youth in France.

Living the life of a bon vivant in the Paris of the 1920s and 1930s, Gunzburg spent money lavishly, and his costume balls featured extravagant sets designed by architects and artists. Gunzburg, who was homosexual and never married, had two known long-term companions, Erik Rhodes, an actor, and artist Paul Sherman.

"In 1926, Niki could be found in Venice at the Excelsior ballroom, dancing a lively Charleston, choreographed by Harlem expatriate Bricktop. He “danced like no one else,” society decorator Billy Baldwin remembered."

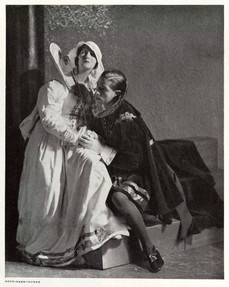

Carl Theodor Dreyer, the Danish film director, met Gunzburg in Paris. This led to their co-production of the expressionistic horror film Vampyr (1932). Loosely based on the vampire stories by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu collected as In a Glass Darkly, the protagonist, Allan Gray, was played by Gunzburg under the screen name Julian West. As Dreyer scholars Jean and Dale D. Drum have observed: "The baron was by no means a talented player, but Dreyer directed him to move through the scenes as though he were in a dream, with very little expression on his face and with all motion slowed down and muffled; in this way he fitted into the mood of the film quite successfully."

Legend states that upon the death of his father, Gunzburg learned the remaining family fortune was non-existent. Left with only the money he had in a checking account, he purchased his passage to America and used what was left to throw a costume ball in July 1934. Co-hosted by Gunzburg and Prince and Princess Jean-Louis de Faucigny-Lucinge, "Le Bal de Valses", aka "A Night at Schoenbrunn", had as its theme the Imperial Court at Vienna in 1860.

The ball took place in Paris’s Bois de Boulogne, on an island, in the midst of an artificial lake. Blanketed to the water’s edge in snow-like white velvet, the island was accessible only by rowboat. Guests first stopped by the Vogue studio to be photographed by Horst P. Horst.

Niki masqueraded as the Archduke Rudolf, Carlos de Beistegui was costumed as Mad King Ludwig of Bavaria, Chanel as the doomed Empress Carlota of Mexico, Prince de Faucigny-Lucinge as Emperor Franz Josef, his wife Baba de Faucigny-Lucinge as Empress Elizabeth, and Elsa Maxwell cross-dressed as Napoleon III. The ball ended at dawn, and a few days later Niki, the Sicilian duke Fulco di Verdura, and the ethereal Russian princess Natalia Paley set sail for America.

"Just before their departure, Horst took a studio portrait of Niki, a mesmerizing image that for succeeding generations has served as a touchstone of male elegance. His dark hair severely parted and slicked back, his enormous eyes gazing penetratingly into the distance, Niki wears around his narrow wrist a Cartier watch fastened by a braided-leather band and, on his pinkie, a hammered-gold ring fashioned for him by Millicent Rogers out of a 24-karat-gold louis.

Between his impossibly attenuated, tapering fingers he holds a nearly spent, smoking cigarette whose long, cylindrical ash miraculously has not dropped—one of the baron’s many “exquisite mannerisms,” decorator Tom Fallon said. A sartorial tic not visible in Horst’s bust-length portrait is Niki’s penchant for sockless ankles, a habit adopted by Billy Baldwin, Bobby Short, Calvin Klein, Thom Browne, and countless men in Palm Beach."

Arriving in America in 1934 together with Fulco di Verdura and Princess Natalie Paley, Gunzburg settled first in California. He was one of many European émigrés who sought refuge in the growing colony of artists in Hollywood. Gunzburg soon abandoned California for Manhattan, which was his home for the remainder of his life.

Gunzburg arrived in New York City on 10 November 1936 and rented an apartment in the Ritz Tower. "Decorator Billy Baldwin was still marvelling three decades later about the baron’s 18th-floor aerie. “I do not know of anything that I have ever seen in my life that was more exciting,” he declared. Furnished with precious and peculiar objects, it featured a library lined in green baize and plastered floor to ceiling with tiny, elaborately framed pictures. Baldwin said of Niki—whose architectural ideal was Amalienburg Palace—“I think that he had in many ways the best judgment about any kind of decoration, from a wastebasket to a palace, of anybody I’ve ever known. He had an immense knowledge … read like a man starving . . . and oddly enough he was also a very hard worker.” Though Niki would supplement whatever paltry income he still had by periodically selling off some of his extraordinary furnishings—an immense Art Nouveau sofa, for example, was lowered through his Ritz Tower apartment’s 18th-floor window and sold to his pal Doris Duke—his straitened circumstances eventually forced him to find regular employment."

Late in 1941, Niki discovered his calling, at 37, when editor in chief Carmel Snow recruited him to join her fashion staff at Harper’s Bazaar, under Diana Vreeland. After working as an editor at Harper's Bazaar and as editor in chief of Town & Country, Gunzburg was appointed senior fashion editor of Vogue in 1949. Chauvinistically, he admitted that office life had its drawbacks. "I want to be in fashion, so I have to work with women, and that's that," he told The New York Times in 1969. "But what it all comes down to is the weekly paycheck, isn't it?" Alexander Liberman, the editorial director of Condé Nast Publications, called Gunzburg "One of the most civilised men in Paris."

Known for his minimalist wardrobe of black, grey, and white, his grey suits were made by Knize & Co., the Viennese tailors. He dressed for the rest of his life in a strict mortuary palette of gray, black, and white, “like an undertaker,” philanthropist Louise Grunwald says—or, from his friend Noël Coward’s perspective, “like a nun.” Gunzburg was named to Vanity Fair's International Best Dressed Hall of Fame in 1971. One Vogue writer described him as:

"A slender, attractive man with a really dry wit, a gift for mimicry, and a sharply developed taste for the simple but cultivated amenities of living."

His luggage bursting with his black Knize suits, Niki would spend a month in France for Vogue every summer, to attend haute couture shows. One of the most treacherous places to be seated during the défilés was beside Niki in the front row. Very dryly, and quietly, behind his hand, lips as immobile as a ventriloquist’s, he would utter the most devastating commentaries, leaving his seatmate collapsing with spastic laughter, while he remained “with an utterly bland, deadpan expression, looking as if he had nothing to do with it,” says Grace Mirabella, whose merchandising editor’s office abutted his. Remembers another close colleague, “He had a very funny, unexpected turn of mind; his witticisms were brief, and they always hit the nail on the head.”

Gunzburg was a summer resident of Highland Lakes, in Vernon Township, New Jersey for the last 20 years of his life. In December 1959, he purchased a two-acre island he called Hemlock, and constructed a causeway and summer house, which he decorated and furnished in a Tyrolean style.

Gunzburg also was a mentor to three up-and-coming fashion designers who would go on to dominate the industry: Bill Blass, Oscar de la Renta, and Calvin Klein. The last-named, whom Gunzburg met in the mid 1960s, was perhaps the baron's most famous protégé, and Klein discussed Gunzburg with Bianca Jagger and Andy Warhol in Interview magazine, published not long after the baron's death:

"He was truly the greatest inspiration of my life ... he was my mentor, I was his protégé – If you talk about a person with style and true elegance – maybe I'm being a snob, but I'll tell you, there was no one like him. I used to think, boy, did he put me through hell sometimes, but boy, was I lucky. I was so lucky to have known him so well for so long."

Recalling one of Calvin Klein's first major fashion shows, Gunzburg said that immediately after the show a nervous Klein sought out his opinions on his new designs, and on whether the event had been a success or failure. The response to his protégé, a wry assessment – chilly, but supportive and polite: "You showed great courage".

Gunzburg died 20 February 1981 at New York Hospital at age 76. He was buried the following spring near his summer home in Glenwood Cemetery, with a small private service at which Blass, de la Renta, and Klein were among the mourners. You can read more about Gunzburg's life and eccentricities in the Vanity Fair article A Taste for Living by Amy Fine Collins.

Comments