Alastair - Muses & the Beau Monde

- Lilium

- Mar 16, 2022

- 3 min read

Hans Henning Otto Harry Baron von Voigt, best known by his nickname Alastair, was a German artist, composer, dancer, mime, poet, singer and translator.

He was born of German nobility in Karlsruhe. In his youth he joined a circus and learned mime. Shortly after leaving school he studied philosophy at Marburg University where he met the writer Boris Pasternak. He was self-taught as an artist, and he was also a proficient dancer and pianist.

He is best known as an illustrator, under the nom de plume "Alastair". His career as an artist was launched in 1914, when John Lane published Forty-Three Drawings by Alastair.

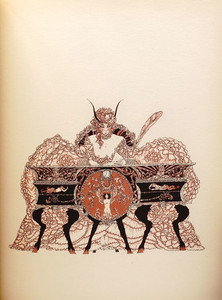

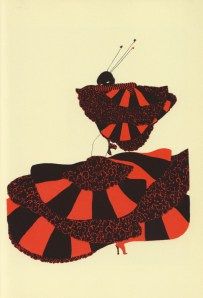

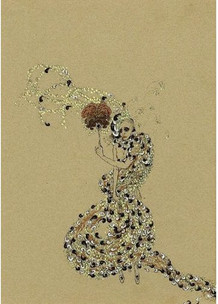

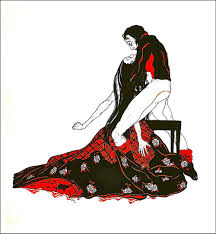

His drawings, which are often decadent in spirit and have the look of Art Nouveau, are influenced somewhat by the drawings of the English artist Aubrey Beardsley, who illustrated works by Oscar Wilde, as Alastair would later do. His ‘serpentine line’ often depicts characters whose outlines are lightly drawn with the main areas filled in with ‘broken dotted lines’. His drawings were in black and white ink, sometimes with one colour added. Alastair's illustrations show a strong influence from the Decadent movement in art and poetry that had begun decades earlier, with the "perverse and sinister" a recurring theme. Intricate decorative elements and fine detail are apparent in his works.

"In his drawings, Alastair took Aubrey Beardsley’s feverish monochromes as a starting point, investing folds of fabric with as much expressive power as faces or gestures. But the page couldn’t monopolise Alastair’s prodigious gifts. His very life was a production in which he would dance at intimate soirees, dressing his own sets and even providing the musical interludes; he was a good enough pianist to duet with the brilliant cellist Pablo Casals."

- James J. Conway, Strange Flowers

Alastair’s fame spread in 1920 with the publication of Wilde's The Sphinx, which contained ten full-page illustrations by him, ‘printed in black and turquoise’. Many of his drawings were inspired by the poems of Wilde, and in 1922 Alastair would illustrate a book of Wilde’s play Salome.

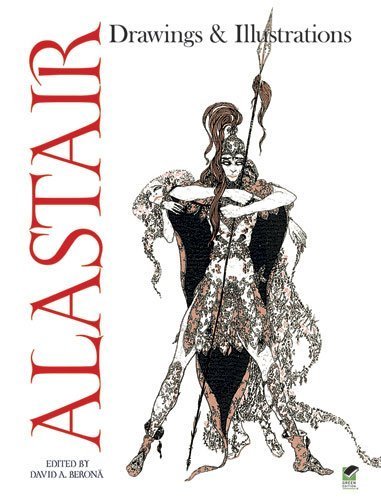

Other books containing Alastair's illustrations include: The Blind Bow-Boy by Carl Van Vechten (1923), in which Alastair depicted the ‘androgynous male’, Fifty Drawings by Alastair (1925) Red Skeletons by Harry Crosby (1928) and "The Fall of the House of Usher" by Edgar Allan Poe (1928).

He also illustrated Manon Lescaut Translated From The French Of Abbé Prevost by D. C. Moylan With Eleven Illustrations by Alastair and An Introduction By Arthur Symons (1928), The Birthday of the Infanta by Oscar Wilde (1928) and Les Liaisons Dangereuses by Choderlos de Laclos (1929).

"Alastair also came with his own costumes. Italian poet Gabriele d’Annunzio recalls a memorable Parisian scene on the eve of World War I, which found the artist dressed in priestly blue brocade robes performing “gothic dances” around a gilded unicorn. Publisher and poet Caresse Crosby relates of her first meeting with Alastair in 1927, “a butler ushered us into a room where there was a black piano with a single candle burning on it. Soon Alastair himself appeared in the doorway in a white satin suit; he bowed, did a flying split and slid across the polished floor to stop at my feet, where he looked up and said, ‘Ah, Mrs. Crosby!’”

- James J. Conway, Strange Flowers

Alastair had at least two public exhibitions of his works during his lifetime, at the Leicester Galleries in 1914 and at the Weyhe Gallery in New York in 1925. During the 1930s, he stopped drawing, only to resume in 1964.

Alastair died in Munich in 1969, aged 82. In his article on Alastair, Conway wrote:

"One of the most remarkable aspects of Alastair’s improbable existence was how few spectators there were for all this performative fabulousness. He was a one-man chamber opera whose audience was just a handful of like-minded friends, or no-one at all. This wasn’t attention-seeking as we understand it, or a cry for help, or even an act of conscious rebellion; it was the magnificent flowering of rare talents and rarer tastes. He was as he was because he could not be otherwise."

Reading Recommendations & Content Considerations

David A. Berona Victor Arwas

Comments