Alfred Gilbert - Gifted Gallery

- Lilium

- Apr 11, 2021

- 7 min read

Sir Alfred Gilbert RA, born 12 August 1854, was an English sculptor and artist.

Alfred Gilbert was born at 13 Berners Street, which was near Oxford Street in central London. He was the eldest child of Charlotte Cole and Alfred Gilbert, who were both musicians. Berners Street was at that time an area popular with artists and musicians: there were shops selling stained glass, carvings, printings and bronze artworks; Ford Madox Brown and Edward Hodges Baily had studios nearby; Leigh's Academy (run by James Mathews Leigh) was nearby, later becoming Thomas J. Heatherley School of Art.

Gilbert's father pushed him to become a surgeon, so he applied to the Royal College of Surgeons and was accepted in 1872. He then went for a scholarship at Middlesex Hospital to work as a surgeon and was rejected, allowing him to pursue his true interest of sculpture. Studying first at the Thomas J. Heatherley School of Art from 1872 until 1873, afterwards he went to the Royal Academy Schools from 1873 until 1875. His fellow students included Frank Dicksee, Johnston Forbes-Robertson, John Macallan Swan, Hamo Thornycroft and J. W. Waterhouse. Eager to learn, he also worked in the studios of Sir Joseph Boehm, Matthew Noble, and William Gibbs Rogers. Gilbert was to credit Boehm and his assistant Édouard Lantéri as his true teachers. Gilbert later travelled to Paris to study at the École des Beaux-Arts under Pierre-Jules Cavelier.

His first work of importance was The Kiss of Victory, which depicted a Roman soldier dying in the arms of Victory. He moved with his family to Rome in order to create the sculpture in marble, attracted by famed sculptors of the Renaissance such as Cellini, Donatello, Giambologna and Verrocchio.

His next work was the trilogy of Perseus Arming, Icarus and Comedy and Tragedy. Perseus Arming (1882) was inspired by a visit to Florence and influenced by Donatello's David and Cellini's Perseus with the Head of Medusa. It was Gilbert's first statue made in bronze. The work was acclaimed and led artist Frederic Leighton to commission Icarus (1884), which was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1884, along with Study of a Head (1882–83). Gilbert later stated to novelist Joseph Hatton that the bronze statues Perseus Arming, Icarus and Comedy and Tragedy (1891–92) formed a trilogy which referenced his own life. Perseus Arming had a huge impact on a new generation of artists, becoming a particular inspiration for the New Sculpture movement, since the method of casting (lost wax) was new to the English milieu and its height of 29 inches was innovative.

Having returned to England, Gilbert took a studio in a complex off Fulham Road, where he built a foundry with fellow sculptors Thomas Stirling Lee and Edward Onslow Ford. His most creative years were from the late 1880s to the mid-1890s, when he created celebrated works such as a memorial for the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria. A massive silver, silver-gilt and rock crystal centrepiece was commissioned by the Officers of the Combined Military Forces as a gift for Queen Victoria on the occasion of her Golden Jubilee in 1887. It was delivered in May 1890. Gilbert described it 'the supremest effort of my life'. A statue of Queen Victoria was also commissioned by the High Sheriff of Hampshire to mark the occasion.

Gilbert's next work of note was the Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain. Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury, a philanthropist, had died in late 1885 and it was swiftly decided to commemorate his life with two monuments, one at Westminster Abbey and another at Cambridge Circus, at the beginning of Shaftesbury Avenue (which was concurrently named after him). The memorial was commissioned in 1886 and officially opened at Piccadilly Circus in London in 1893.

Gilbert had accepted the commission with assurances that he would be given used gunmetal to melt down and reuse, however the government did not supply him with it. He had already produced the casts, so he was forced to buy copper to use instead, which meant that he took a substantial financial hit; the fountain should have cost £3,000 (equivalent to about £388,000 in 2021) and in the end the figure was £7,000 (equivalent to about £905,000 in 2021), with Gilbert being forced to make up the difference. It was only because he had been experimenting with different techniques that he was able to cast aluminium, a then new material which he used to create the statue of Anteros which topped the sculpture.

It is commonly believed that the statue depicts Eros, but it is actually his brother Anteros, the avenger of unrequited love. The fountain is now well-regarded and seen as a national treasure, but at the time it was controversial, with opinions on its value mixed. The mainstream media criticised the design of the fountain which led to passing flower girls being drenched in water and hooliganism meant it needed to be guarded for a year. Eight drinking cups on chains had been provided for pedestrians to quench their thirst and Gilbert stated that just one day after the opening, only two cups remained. He referred to the "painful experience of witnessing the utter failure of my intention and design."

As well as sculpture, Gilbert explored other techniques such as goldsmithing and damascening. He painted watercolours and drew book illustrations. Gilbert also created spoons, cups, dishes and jewellery; many of his designs can be seen in the collection of Stichting van Caloen on display at Loppem Castle, Belgium and the Victoria & Albert museum, London (right).

He was made a member of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1892, yet his personal life was beginning to unravel as he took on too many commissions and entered into debt, whilst at the same time his wife's mental health deteriorated.

n 1892, Gilbert was asked by the Prince (later Edward VII) and Princess of Wales (Alexandra of Denmark) to build the tomb for their recently deceased eldest son Prince Albert Victor in St George's Chapel, Windsor. Prince Albert Victor had been heir to the throne and died of pneumonia resulting from contracting influenza during the 1889–1890 flu pandemic. The tomb has been described by a critic as "the finest single example of late 19th-century sculpture in the British Isles". A recumbent effigy of the prince wearing a Hussar uniform lies above the tomb. Kneeling over him is an angel, holding a heavenly crown. The tomb is surrounded by an elaborate railing, with figures of saints. The perfectionist Gilbert spent too much time and money on the commission. Five of the saint figures were only completed with "a greater roughness and pittedness of texture" after his return to Britain in the 1920s.

By 1898, Gilbert was in debt and the number of complaints from clients asking for completed works was increasing. Instead of finishing the tomb for Prince Albert Victor, which only had seven of the twelve saints around it, Gilbert took another royal commission, namely building the mortuary chapel for Prince Henry of Battenberg. Ultimately, Gilbert was forced to file for bankruptcy in 1901. He sent his family before him to Bruges in Belgium and stayed behind to pack up his studio, destroying many casts in the process.

Marion Spielmann, a contemporary art critic, wrote in 1901

"his taste is so pure, his genius so exquisitely right, that he may give full rein to his fancy without danger where another man would run riot and come to grief".

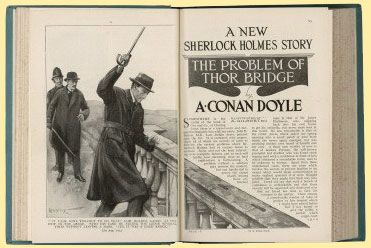

During World War I, Gilbert remained in Bruges. Three illustrations for Arthur Conan Doyle's short story "His Last Bow. The War Service of Sherlock Holmes" were published in The Strand Magazine in 1917 and in 1921 three more for "The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone".

He married his housekeeper Stéphanie Quaghebeur on 1 March 1918 and they moved to Rome together in 1924. In the early 1920s, Gilbert had been largely forgotten about in England and was assumed to have died, since he had fled to Europe decades before. However, he was still receiving a civil list pension and when the journalist Isabel McAllister took an interest in him, she was able to find him easily.

McAllister commented in 1932 "One must be entirely loyal to him, and never admit faults to those who ... are always ready to look out for them". She decided to write his biography and campaigned for his re-acceptance in English high society. Writing to King George V and various dignitaries, she promoted Gilbert's talents, arguing it was time for him to finish the tomb of Prince Albert Victor and also that he was the perfect person to take the commission to create a memorial to Queen Alexandra, who had died in 1925. The King was glad to hear news of his old acquaintance and Lady Helena Gleichen became Gilbert's promoter, offering that he could use her studio at St James Palace if the funds could be raised to bring him from Italy.

He returned to England and finally completed the tomb of Prince Albert Victor, as well as taking on new commissions such as the Queen Alexandra Memorial, This memorial captured his imagination since he saw the major public artwork as his swan song. Furthermore, Alexandra had been a firm friend of his, supporting him financially even when he failed to complete the tomb for her eldest son.

The sculpted fountain of the memorial blended art nouveau and gothic styles, and was built into the wall of Marlborough House. It was officially unveiled on 8 June 1932, which was announced as Alexandra Rose Day . It depicts three figures representing Faith, Hope, and Charity who are helping a maiden move across the stream of life. Gilbert was knighted the day afterwards and was also readmitted into the Royal Academy. His return to favour was complete.

Sir Alfred Gilbert died in 1934, at the age of 80. At the time of his death, Gilbert was one of the most well-known figures in English society and there were plans to make a film about him. He was then disregarded for decades, until critic Richard Dorment published a biography of Gilbert in 1985, which was followed by a retrospective at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1986. Gilbert was a central inspiration for the New Sculpture movement and in the 21st-century is regarded as one of the foremost sculptors of the Victorian age.

Like many others, I had walked past Gilbert's works often unaware. It was in John Betjeman's documentary 'A Passion for Churches' that I first saw his work in detail. At 30:41 minutes in Mr Betjeman takes us to the parish church of Sandringham, the Queens country estate and amongst the jewel incrusted bible and the solid silver pulpit is a small figure of saint George "...you can tell by the swirls and the curves who the sculptor was.."

I fell in love with that figure and was astonished when I stumbled across a copy in the Pre-Raphaelite room at the Ashmolean Museum, the intricate detail of his armour and his languid pose combined makes it one of the most beautiful pieces of art I have ever seen.

Reading Recommendations & Content Considerations

Richard Dorment The Fine Art Society

Comments