Bronislava Nijinska - Muses & the Beau Monde

- Lilium

- Mar 31, 2021

- 7 min read

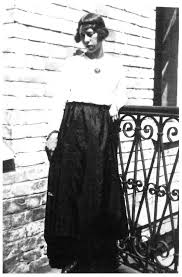

Bronislava Nijinska, born January 8, 1891, was a Polish ballet dancer, and an innovative choreographer. She came of age in a family of traveling, professional dancers. Nijinska played a pioneering role in the broad movement that diverged from 19th-century classical ballet. Her introduction of modern forms, steps, and motion, and a minimalist narrative, prepared the way of future works.

Bronislava Nijinska was the third child of the Polish dancers Tomasz [Foma] Nijinsky and Eleonora Nijinska (maiden name Bereda), who were then traveling performers in provincial Russia. Following serious home training, in 1900 she entered at the age of nine the state ballet school in the Russian capital, the same state-sponsored school for performing arts her brother Vaslav had entered two years before.

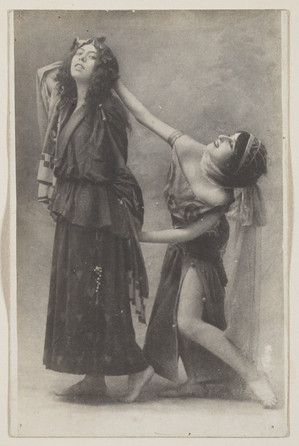

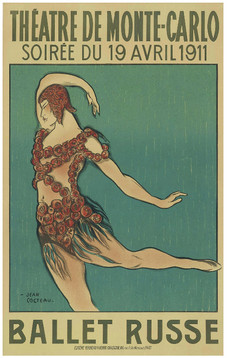

In 1908 she graduated as an 'Artist of the Imperial Theatres'. It was a government formality which assured her of financial security and the privileged life of a professional dancer. An early breakthrough came in Paris in 1910 when she joined her brother as a member of Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. For her dance solo Nijinska created the role of Papillon in Carnaval, a ballet written and designed by Michel Fokine.

"Bronislava Nijinska, known as Bronia, was very like her brother Vaslav Nijinsky. She was blonde and wore her straight hair screwed into a tight little roll. She had pale eyes and pouting lips, wore no makeup at all and had not shaved off her eyebrows as most of us had in those days. ... Bronia was obstinate and once she had made up her mind nothing in the world would move her. She was brilliantly clever and inventive. No music seemed to present any difficulties for her, but her style of movement was even more pronounced and idiosyncratic than that of Massine, and she was not an easy person to work for in class or at rehearsal ... Her system of training seemed to depend more on improvisation than on traditional methods of technique ... To watch her devise a sequence of steps and movements for one of her ballets was most interesting. I liked her, in spite of her moodiness and lack of humor. There were two of us in the company whom Diaghilev could always make cry whenever he wished, Nijinska and myself."

- Lydia Sokolova

Nijinska married twice. Her first husband, Alexandre Kochetovsky, was a fellow dancer for Ballet Russes. She calls him 'Sasha' in her Early Memoirs. Married in London in 1912, they soon left for Russia. They would go on to have two children: their daughter Irina Nijinska in 1913 in Saint Petersburg (called 'Irushka'), and Leon Kochetovsky, their son in 1919 in Kiev (called 'Levushka'). They would separate after the birth of their son.

She assisted her brother Vaslav Nijinsky as he worked on his controversial choreography for L'Après-midi d'un faune, which Ballets Russes premiered in Paris in 1912. Similarly, she aided him in his creation of the 1913 ballet The Rite of Spring.

When her brother suddenly married, Diaghilev terminated his position at Ballets Russes. Nijinska left the company in solidarity with him. In early 1914 Vaslav Nijinsky started a new ballet company in London: Saison Nijinsky. Bronislava offered her assistance, yet learned there was only a short time to prepare for its premiere performance. Vaslav had signed a contract to open at a dance hall, the London Palace Theatre, in four and a half weeks. Nijinska quickly decided to return to Russia to recruit the cast, but Warsaw was where the experienced dancers were found. She with others explained her brother's innovative choreographies. She directed rehearsals, as musicians, scores, sets and costumes were arranged.

Nijinska herself was to perform with Vaslav in Le Spectre de la rose. Its anticipated premiere was well received. Vaslav's brilliant dancing drew prolonged applause. After performing for two weeks, however, a business dispute developed. It arose when Nijinsky became sick and was unable to perform for a few days. It led the theater owner Alfred Butt to cancel the company's season. Brother and sister became separated for seven years, first by World War I, then by the Russian Revolution, followed by the Russian Civil War. There was little chance for communication as mail service first became irregular and then discontinued. In 1921 they met again in Vienna, where they remained together for a short time.

Nijinska developed her own art in Petrograd and Kiev during the great war, revolution and civil war. While performing in theaters, she worked independently to design and stage her first choreographies. Nijinska started a ballet school on progressive lines in Kiev. She published her writing on the art of movement. In 1921 she fled Russian authorities.

Rejoining the Ballets Russes in 1921, Diaghilev appointed her the choreographer of this now influential company based in France. Nijinska thrived, creating several popular, cutting-edge ballets to contemporary music. In 1923, with a score by Igor Stravinsky she choreographed her iconic work Les noces (The Wedding). Nijinska took prominent roles in many of her own dance designs. Accordingly, she performed as the Lilac Fairy in The Sleeping Beauty (1921), the Fox in Le Renard (1922), as the Hostess in Les Biches (1924), as Lysandre in Les Fâcheux (1924), and as the Tennis Player in Le Train Bleu (1924).

Nijinska's second marriage in 1924 was to Nicholas Singaevsky (called 'Kolya'). A few years her junior, he'd been a former student and dancer at the 'Ecole de Mouvement' she had founded in Kiev following the Russian revolution. He, too, had left Russia. They met again as exiles in Monte Carlo. He became associated with Ballets Russes as a dancer. They were married in 1924. During their four decades together, he often worked in production and management, acting as her business partner in staging her various ballet productions and other projects. Later in America he also translated for her, especially when she taught at the ballet studio.

Starting in 1925, with a variety of companies and venues she designed and mounted ballets in Europe and the Americas. Among them: Teatro Colón, Ida Rubinstein, Opéra Russe à Paris, Wassily de Basil, Max Reinhardt, Markova-Dolin, Ballet Polonaise, Ballet Theatre, the Hollywood Bowl, Jacob's Pillow, Serge Denham, Marquis de Cuevas, as well as her own companies.

Nijinska and her family were in London when World War II started with the combined Nazi and Soviet invasion of Poland (September 1939). She had a contract to co-direct the dance sequences on a new film, Bullet in the Ballet, but it was cancelled due to war. Fortunately, an offer from promoter de Basil allowed them to make their way back to the United States. She eventually established a new residence in Los Angeles and continued working in choreography and as an artistic director, teaching in her studio.

Allegra Kent recalls starting ballet lessons in 1949 when she was twelve. Madame Nijinska was a "nice-looking woman in black lounge pajamas with a long cigarette holder". She counted time "ras, va, tri" in Russian. "Her husband was simultaneously translating everything she said into English." Because of her commanding presence in classes, "The world began and ended right there in that moment." After a year with her daughter Irina Nijinska, Kent studied with 'Madame' herself. She learned "not to fear competing with men" and that "the light look of dance was merely the surface of a sculpture-there was a mixture of steel and quicksilver at the heart."

During the 1960s she staged revivals of her Ballets Russes-era creations for The Royal Ballet in London. In 1964 Frederick Ashton of The Royal Ballet asked Nijinska to stage a revival of her ballet Les Biches at Covent Gardens. The staging of the revived Les Biches went well. Two years later, Ashton asked her to return to London and stage her Les noces for his company. Below is a small interview clip of an Ashton talking about the influence of Nijinska.

These 1964 London productions, according to dance critic Horst Koegler, "confirmed her reputation as one of the formative choreographers of the 20th century." In 1934 Ashton had expressed his own opinion:

"Her achievements have proved to me time and again that through the medium of classical ballet any emotion may be expressed. She might be called the architect of dancing, building her work brick by brick into the amazing structures that result in masterpieces like Les noces."

Following these London events, Nijinska was repeatedly invited to revive several of her ballets. She staged Les Biches in Rome in 1969, and in Florence and Washington in 1970. Also Les Biches, and a revised version of Chopin Concerto and Brahms Variations, for the Center Ballet of Buffalo in 1969.

Les noces was staged in 1971 in Venice, where during a rehearsal at the Teatro Fenice, she celebrated her eightieth birthday onstage. Between 1968 and 1972, Nijinska saw performances of Les Biches, Les noces, Brahms Variations, Le Marriage d'Aurore, and Chopin Concerto for ballet companies in the United States and in Europe.

In the last year of her life Nijinska devoted to finishing memoirs about her early life. She had notebooks of her writings and had kept theatrical programs throughout her career. A manuscript of 180,000 words was left completed.

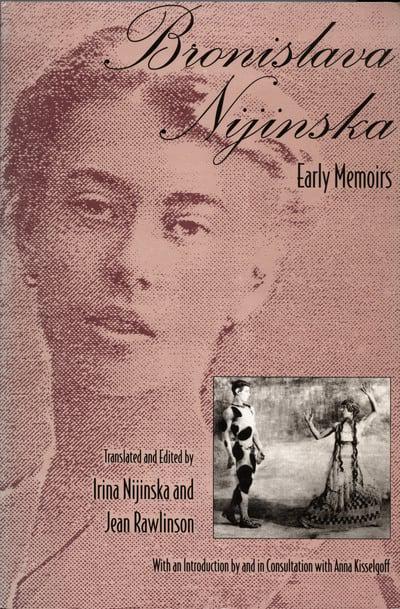

Following her death in early 1972, Bronislava Nijinska's daughter Irina Nijinska was named her literary executor. Then she and Jean Rawlingson edited and translated the Russian manuscript into English. They edited the text, and saw it through to publication. The book Early Memoirs appeared in 1981. These writings describe in detail her early years traveling in provincial Russia with her dancer parents, her brother Vaslav's development as a dancer, her schooling and first years as a professional in the Diaghilev era of Russian ballet, and her work assisting her brother in his choreography. During her life, she had published a book and several articles on ballet.

The full autobiographical story of her own career, however, is contained in another set of her memoirs, continuing from the 1914 close of her Early Memoirs. She also left a set of notebooks on ballet and other writings, which remain unpublished.

Reading Recommendations & Content Considerations

A Dancer's Legacy Early Memoirs

Comments