George Barbier - Muses & The Beau Monde

- Lilium

- Oct 7, 2020

- 6 min read

George Barbier, born in Nantes, France on 16 October 1882, was one of the great French illustrators of the early 20th century.

Little is known of Barbier’s personal life, but it is known that he started his career when he attended the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in the atelier of Jean Paul Laurens in 1907. He would often be found reproducing paintings housed in the local museum by notable artists such as Antoine Watteau and Ingres. He made his entrance into the Nantes art world through the local Société des Amis des Arts, with early commissions from enthusiastic patrons such as Alphonse Lotz-Brissonneau.

He is believed to have spent several years in London before enrolling in the Paris studio of Jean‐Paul Laurens at the Académie Julien. His time in England is shrouded in mystery, but his personal library that was dispersed upon his death housed numerous titles illustrated by leading English illustrators such as William Blake, Charles Ricketts, Gustave Doré, Arthur Rackham, and the famous Aubrey Beardsley. Barbier also owned personal correspondence by Beardsley, as well as some of his original illustrations for works by Edgar Allan Poe. Their influence on Barbier was profound. His connection to England may have influenced his decision to adopt an Anglicised form of his name (Georges to George).

In 1908 the famous Paris couturier Paul Poiret published his first album of new styles, illustrated by Paul Iribe, which would revolutionize women’s fashion. Gone were the whalebone corsets and petticoats, replaced by daring long gowns that revealed the female form. Vogue magazine quoted designer Jean Worth as proclaiming Poiret’s designs “suitable for the women of uncivilized tribes. If we adopt them, let us ride on camels and ostriches.” Poiret’s designs prevailed, and were bolstered by the Paris debut of the Ballets Russes under the direction of Sergei Diaghilev in May 1909. Its dramatic and colourful costumes by Léon Bakst conquered the Paris fashion scene.

"Un élégant jeune homme blond, tranquille et réservé (an elegant blond young man, quiet and reserved)."

- Vogue of Barbier

Barbier was 29 years old when he mounted his first exhibition in 1911 and was subsequently swept to the forefront of his profession with commissions to design theatre and ballet costumes, to illustrate books, and to produce haute couture fashion illustrations.

The new fashions inspired by Poiret and the Ballets Russes gave birth to the publication of two new fashion journals in 1912: Journal des dames et des modes and Gazette du bon ton. These two exclusive fashion magazines were richly illustrated with coloured fashion plates using the colour stencilling technique known as pochoir.

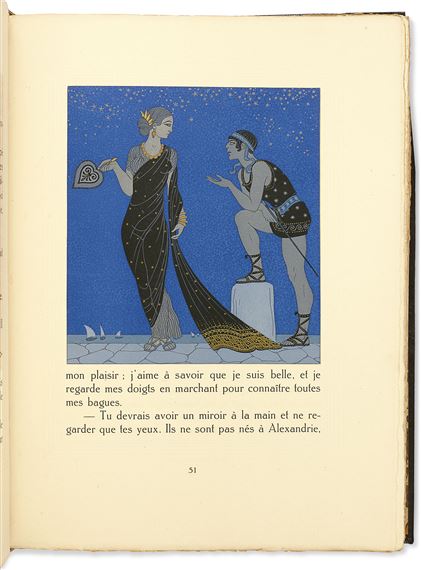

Barbier’s fashion illustrations drew upon a variety of influences and themes, including classical Greece and its mythology, carnivals and masquarades of 18th century Venice, and orientalism. His illustrations often invoked an air of mystery, sometimes suggestive and at other times humorous, while incorporating the latest designs from the Paris ateliers.

The pochoir technique used to create the fashion plates generated images that were especially rich in colour and texture. This methodology was routinely used in de luxe French publication of books and journals throughout the Art Deco period, but faded from use with the introduction of colour photography in the 1930s.

He created over a hundred jewellery designs for his friend, the famous Paris jeweller Louis Cartier. In 1914 Cartier commissioned him to draw an invitation card for an exhibition at La Maison Cartier. Barbier’s design, La femme avec une panthère noire, featured a classical Greek figure, attired in an elegant Paul Poiret gown, accessorized by the presence of a black panther. This stylized panther has been the iconic symbol of the La Maison Cartier since 1917. Barbier also worked on the design of Renault’s Vivastella model, catalogue covers for the Paris clothier High Life Tailor, menu covers for The French Line of transatlantic steamships, an almanac for the American merchant John Wanamaker, and illustrations for the Paris furrier Fourrures Max.

While generating vibrant colour plates, the technique had its limitations in that it did not easily accommodate shading, and it was a slow, labour‐intensive and expensive colouring process. At the height of its popularity over thirty graphic design studios in France employed upwards of six hundred workers to colour the pochoirs.

For the next 20 years Barbier led a group from the Ecole des Beaux Arts who were nicknamed byVogue "The Knights of the Bracelet"—a tribute to their fashionable and flamboyant mannerisms and dandyish style of dress, and their common practice of sporting a bracelet. Included in this élite circle were Bernard Boutet de Monvel and Pierre Brissaud (both of whom were Barbier's first cousins), Paul Iribe, Georges Lepape, and Charles Martin.

"George Barbier is one of the most valuable and most significant artists of our time, so rich in all kinds of talent and original ideas. When our age is past…it will take just a few drawings of Barbier to revive the taste and spirit of our time."

- Edmond Jaloux, Novelist, Critic

Below from 2013, exhibition curator Arthur Smith takes us on a tour of the Fisher Library's exhibition 'Chevalier du bracelet': George Barbier and his illustrated works.

Here is a link to a video from the YouTube channel of Robert Wu where he shows his binding of

George Barbier's Fetes Galantes. Wu is not only an incredible book binder (be still my beating heart) but also a cellist and pianist. On his channel is other book bindings he's made including Shakespeares King Lear and the Portrait of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde.

Among the Parisians captivated by the Ballets Russes and its principal dancers Vaslav Nijinsky and Tamar Karsavina was Barbier, who illustrated two exquisite albums devoted to the dancers. Dessins sur le danses de Vaslav Nijinsky was published in 1913, followed by Album dédié à Tamar Karsavina in 1914.

During his career Barbier turned his hand to jewellery, designing more pieces for Cartier, glass and wallpaper design, wrote essays and many articles for the prestigious Gazette du bon ton. In the mid-1920s he worked with Erté to design sets and costumes for the Folies Bergère and in 1929 he wrote the introduction for Erté's acclaimed exhibition and achieved mainstream popularity through his regular appearances in L'Illustration magazine.

Barbier’s passion for the theatre and ballet dominated much of his professional life for the following two decades, as he became one of the leading costume designers in Paris. His reputation extended across the Atlantic, sending his designs via the costume design house Max Waldy to be produced by the Brooks Costume Company in New York. Among his creations were costumes for Rudolph Valentino for his leading role in the silent film Monsieur Beaucaire in 1924.

Valentino was the embodiment of the 18th century gentleman envisioned by Barbier in his illustrations and costumes. He wrote of Valentino: “The face of the famous actor is light gold in colour; the eyes of velvet shine with charming guile. The attractiveness of this fine face lies not only in the regular features, but also in the caressing, sensual expression that veils his look, animates his nostrils, tightens his lips and leaves few women indifferent.”

Barbier also created costume and set designs for risqué revues at Les Folies‐ Bergère and Casino de Paris, including a scene for Josephine Baker’s 1930 performance in the revue Paris qui remue.

"By epitomising the more refined fantasies of the Parisian world of pleasure during the 1920s, he became the most haunting of Art Deco artists…Recognised as one of the master decorators of the time, he found his services in demand in many fields, but his specialties remained theatrical costumes and settings and above all book decoration…Barbier was a supreme decorative designer, whose art centred on the human figure, displayed in a thousand settings and costumes."

- Gordon Ray, Scholar, Collector

Barbier died in 1932, fifty years old and at the very pinnacle of his success. As a popular mainstream artist, his work was known in both Europe and America. Aside from his design work, Barbier also wrote influential articles and essays on the topic of art and design. Some of Barbier’s most renowned works are illustrations for books such as Fetes Galantes by Paul Verlaine and works by Charles Baudelaire. He is buried in Cemetery Miséricorde, Nantes.

Barbier had continued to work on several projects during his illness. His illustrated edition of Choderlos de Laclos’ Les liaisons dangereuses was published posthumously in 1934. His friend and fellow illustrator Georges Lepape completed his illustrations for Pierre Louÿs’ Aphrodite which was published in 1954.

Reading Recommendations & Content Considerations

Edited by Master of Art Deco

F. Mayer & F. Harlow Pie Books

Comments