J.C. Leyendecker - Muses & The Beau Monde

- Lilium

- Sep 9, 2020

- 6 min read

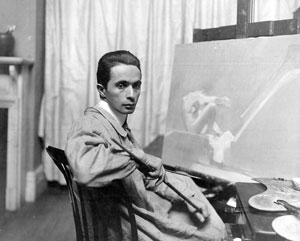

Joseph Christian Leyendecker was a German-American illustrator. He is considered to be one of the pre-eminent American illustrators of the early 20th century.

Leyendecker was born on March 23, 1874, at Montabaur in Western Germany, a tiny village 18km east of the Rhine. In 1882, the Leyendecker family emigrated to Chicago, Illinois. After working in late adolescence for a Chicago engraving firm, J. Manz & Company, and completing his first commercial commission of sixty Bible illustrations for the Powers Brothers Company, Leyendecker sought formal artistic training at the Chicago Art Institute.

In 1895 the April-September issue of Inland Printer had an introduction to J.C. Leyendecker. The article described his work for J. Manz & Company as well as his intention to study in Paris. The article also featured a sketch and two book covers he had illustrated. In this same year, J.C. Leyendecker created his first poster. The poster was for the book One Fair Daughter by Frank Frankfort Moore.

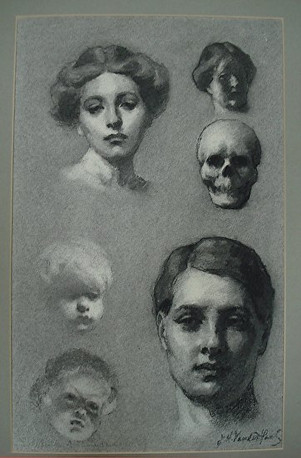

After studying drawing and anatomy under John H. Vanderpoel at the Chicago Art Institute, J. C. and his younger brother Frank enrolled in the Académie Julian in Paris for a year, where they were exposed to the work of Toulouse-Lautrec, Jules Chéret, and also Alphonse Mucha, a leader in the French Art Nouveau movement.

Frank was eighteen when he went to Paris with his brother, not only to study but also to provide companionship. A charcoal study of Frank was the catalog cover of Joseph Leyendecker's one-man exhibition at the Salon Champs du Mars in April 1897.

In 1899, Leyendecker and his brother returned to America and set up residence in an apartment in Hyde Park, Illinois. They had a studio in Chicago's Fine Arts Building at 410 South Michigan Ave.

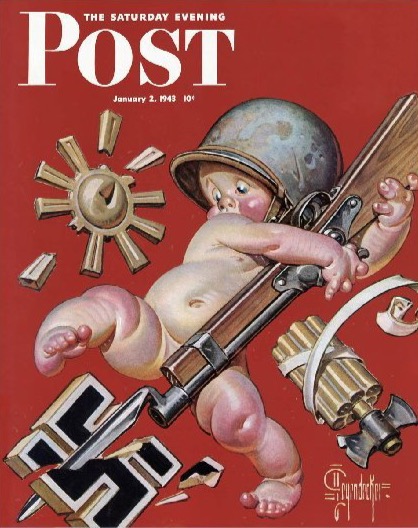

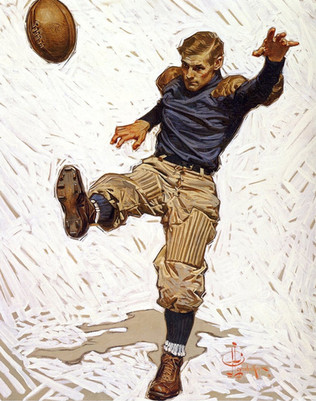

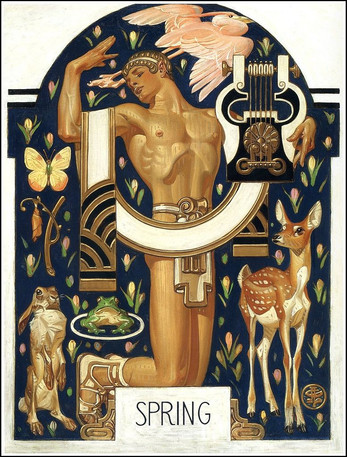

On May 20 of that year, Leyendecker received his first commission for a Saturday Evening Post cover – the beginning of his forty-four-year association with the most popular magazine in the country. Ultimately he would produce 322 covers for the magazine, introducing many iconic visual images and traditions including the New Year's Baby, the pudgy red-garbed rendition of Santa Claus, flowers for Mother's Day, and firecrackers on the 4th of July.

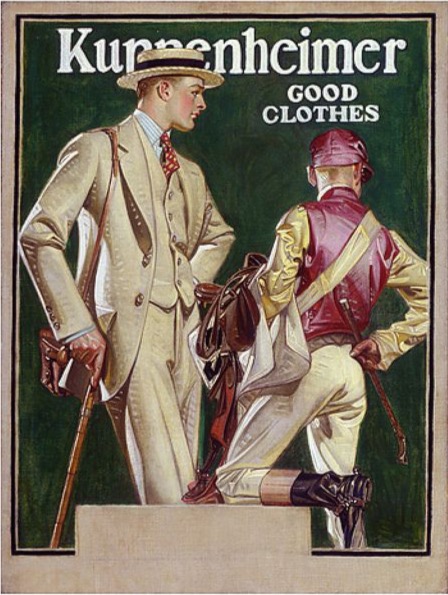

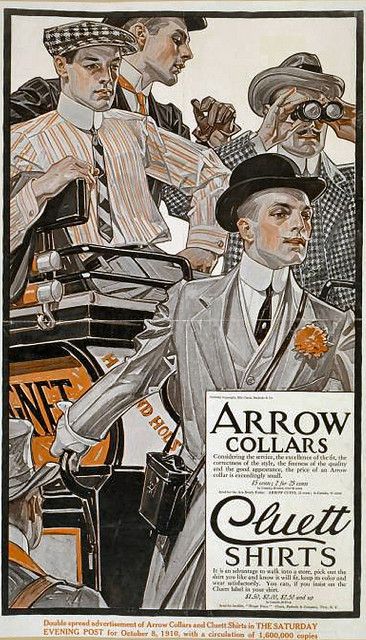

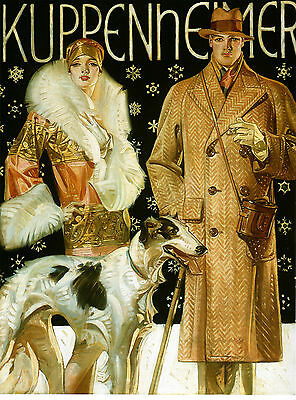

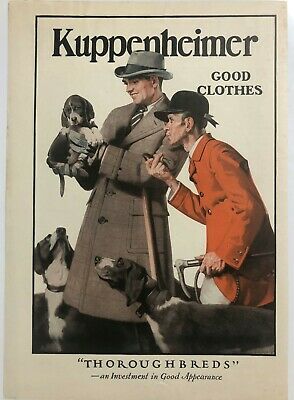

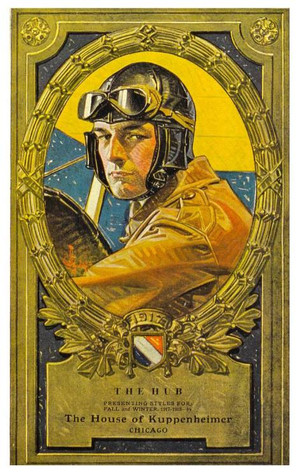

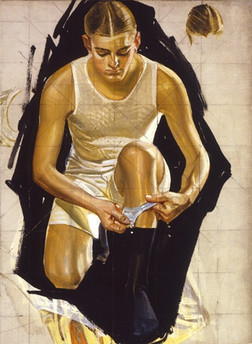

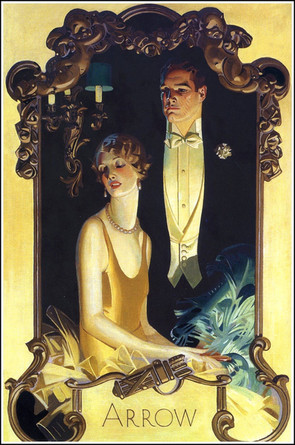

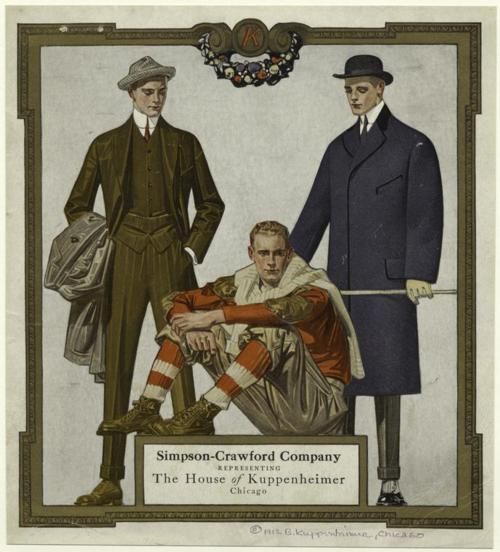

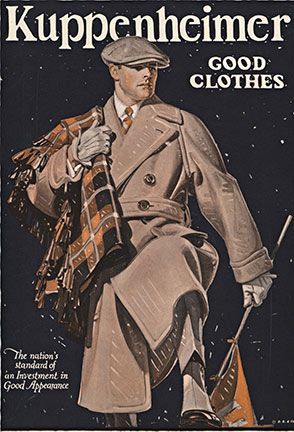

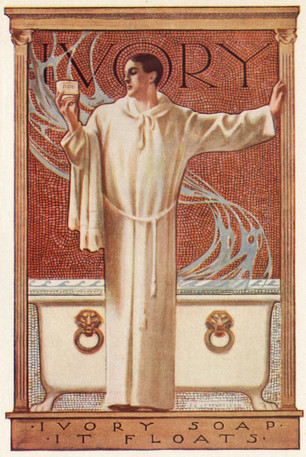

In 1900, Leyendecker and his siblings Frank and Mary moved to New York City, then the center of the US commercial art, advertising and publishing industries. During the next decade, both brothers began lucrative long-term working relationships with apparel manufactures including Interwoven Socks, Hart Schaffner Marx, B. Kuppenheimer & Co. and Cluett Peabody & Company. The latter resulted in Leyendecker's most important commission when he was hired to develop a series of images of the Arrow brand of shirt collars.

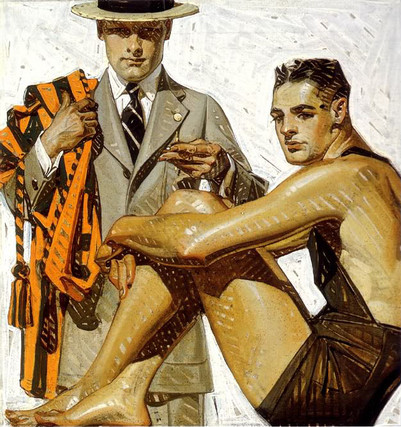

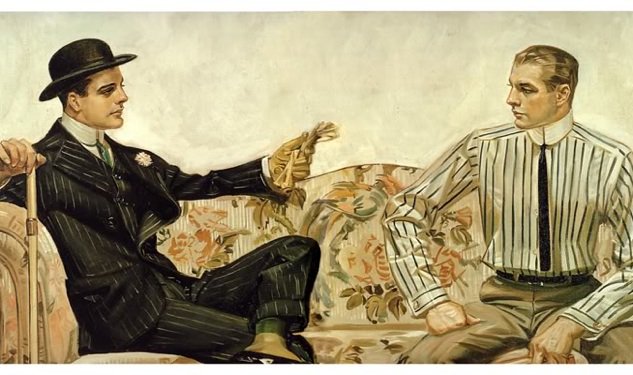

Leyendecker's Arrow Collar Man, as well as the images he later created for Kuppenheimer Suits and Interwoven Socks, came to define the fashionable American male during the early decades of the twentieth century. One day in 1903, a young Ontarian named Charles Allwood Beach came looking for work and discovered his destiny, he met Leyendecker, who often used his favourite model and then partner Charles Beach in his illustrations.

Many biographers have speculated on J. C. Leyendecker's sexuality (more recent research has found more conclusive evidence), often attributing the apparent homoerotic aesthetic of his work to a homosexual identity. Without question, Leyendecker excelled at depicting male homosocial spaces (locker rooms, clubhouses, tailoring shops) and extraordinarily handsome young men in curious poses or exchanging glances. Leyendecker never married, and he lived with another man, Charles Beach, for much of his adult life. Beach, the original model for the famous Arrow Collar Man, is assumed to have been his lover.

"...The Arrow Collar Man developed a singular identity, equal parts jock and dandy, who supposedly received more fan letters than silent film heartthrob Rudolph Valentino. To top things off, Leyendecker’s men were often modelled after his lover and lifetime companion, Charles Beach, making their secret romance a front-page feature across the U.S."

- Hunter Oatman-Stanford, Collectors Weekly

In 1914, the Leyendeckers, accompanied by Charles Beach, moved into a large home and art studio in New Rochelle, New York, where J.C would reside for the remainder of his life. During the first World War, in addition to his many commissions for magazine covers and men's fashion advertisements, J. C. also painted recruitment posters for the United States military and the war effort.

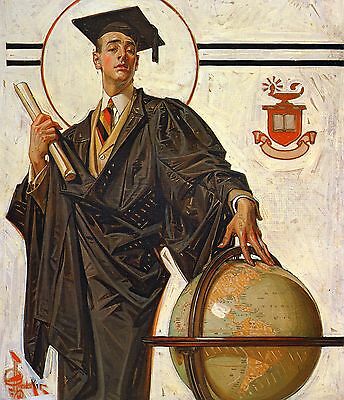

The 1920s were in many ways the apex of Leyendecker's career, with some of his most recognisable work being completed during this time. Modern advertising had come into its own, with Leyendecker widely regarded as among the pre-eminent American commercial artists. This popularity extended beyond the commercial, and into Leyendecker's personal life, where he and Charles Beach hosted large galas attended by people of consequence from all sectors. The parties they hosted at their New Rochelle home/studio were important social and celebrity making events.

As the 1920s marked the apex of J. C. Leyendecker's career, so the 1930s marked the beginning of its decline. Around 1930–31, Cluett, Peabody, & Co. ceased using Leyendecker's illustrations in its advertisements for shirts and ties as the collar industry seriously declined after 1921. During this time, the always shy Leyendecker became more and more reclusive, rarely speaking with people outside of his sister Mary Augusta and Charles (Frank had died in 1924).

Perhaps in reaction to his pervasive popularity in the previous decade, or as a result of the new economic reality following the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the number of commissions Leyendecker received steadily declined. In 1936, the editor at the Saturday Evening Post for all of Leyendecker's career up to that point, George Horace Lorimer, retired, and was replaced by Wesley Winans Stout and then Ben Hibbs, both of whom rarely commissioned Leyendecker to illustrate covers.

Leyendecker's last cover for the Saturday Evening Post was of a New Year Baby for January 2, 1943, thus ending the artist's most lucrative and celebrated string of commissions. New commissions continued to filter in, but slowly. Among the most prominent were posters for the United States Department of War, in which Leyendecker depicted commanding officers of the armed forces encouraging the purchases of bonds to support the nation's efforts in World War II.

Due to his fame as an illustrator, Leyendecker was able to indulge in a very luxurious lifestyle which in many ways embodied the decadence of the Roaring Twenties. However, when commissions began to wane in the 1930s, he was forced to curtail spending considerably. By the time of his death, Leyendecker had let all of the household staff at his New Rochelle estate go, with he and Beach attempting to maintain the extensive estate themselves.

While Beach often organized the famous gala-like social gatherings that Leyendecker was known for in the 1920s, he apparently also contributed largely to Leyendecker's social isolation in his later years. Beach reportedly forbade outside contact with the artist in the last months of his life.

J.C. Leyendecker died on July 25, 1951, at his estate in New Rochelle of an acute coronary occlusion. Leyendecker left a tidy estate equally split between his sister and Beach. Charles Allwood Beach died of a heart attack on 21 June 1954 at New Rochelle.

As the premier cover illustrator for the enormously popular Saturday Evening Post for much of the first half of the 20th century, Leyendecker's work both reflected and helped mould many of the visual aspects of the era's culture in America. The mainstream image of Santa Claus as a jolly fat man in a red fur-trimmed coat was popularised by Leyendecker. The tradition of giving flowers as a gift on Mother's Day was started by Leyendecker's May 30, 1914 Saturday Evening Post cover depicting a young bellhop carrying hyacinths.

Leyendecker was a chief influence upon, and friend of, Norman Rockwell, who was a pallbearer at Leyendecker's funeral. In particular, the early work of Norman Rockwell for the Saturday Evening Post bears a strong superficial resemblance to that of Leyendecker. While today it is generally accepted that Norman Rockwell established the best-known visual images of Americana, in many cases they are derivative of Leyendecker's work, or reinterpretations of visual themes established by Rockwell's idol.

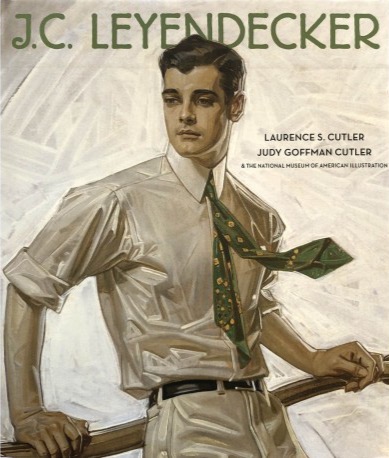

Reading Recommendations & Content Considerations

by by

L.S. Cutler & J. Goffman Cutler Michael Schau

Below is a link to the article by Hunter Oatman-Stanford for Collectors Weekly which includes a detailed interview with Alfredo Villanueva-Collado, a former literature professor at the City University of New York and obsessed collector of J.C. Leyendecker.

Comments