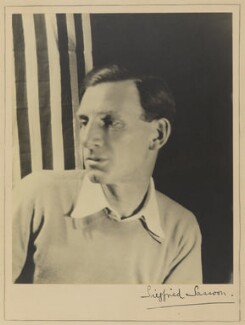

Siegfried Sassoon - Muses & The Beau Monde

- Lilium

- Feb 12, 2020

- 4 min read

Updated: Sep 13, 2020

Siegfried Sassoon, born 8 September 1886, was an English writer, poet and solider.

Siegfried was born to a Jewish father and an Anglo-Catholic mother, and grew up in Matfield, Kent in the neo-gothic mansion named "Weirleigh" (named after its builder, "The Father of Cat Fancy" Harrison Weir).

His father, Alfred Ezra Sassoon, son of Sassoon David Sassoon, was a member of the wealthy Baghdadi Jewish Sassoon merchant family but for marrying outside the faith, Alfred was disinherited.

Siegfried's mother, Theresa, belonged to the Thornycroft family, sculptors responsible for many of the best-known statues in London—her brother was Sir Hamo Thornycroft, one of the youngest members of the Royal Academy of Arts.

There was no German ancestry in Siegfried's family; his mother named him Siegfried because of her love of Wagner's operas. His middle name, Loraine, was the surname of a clergyman with whom she was friendly.

While Siegfried is best known to the world as a war poet and first known to me as the love of Stephen Tennant's life, I wanted to share two pieces of his literature that have resonated with me the most, Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man and The Old Century.

Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man

Prior to this first novel, Siegfried was known exclusively for his poetry of World War I. The book is a depiction of his early years presented in the form of an autobiographical novel, (much of the material for the novel came from Sassoon's own diaries), with false names being given to the central characters, "Aunt Evelyn", a fictionalised representation of his mother Theresa and Sassoon himself, who appears as the narrator and main character "George Sherston".

The story is a series of episodes in the youth of George Sherston, ranging from his first attempts to learn to ride to his experiences in winning point-to-point races. It is the descriptions of this youth, from riding his horse home on a golden summers eve, the soft light of an early morning and the annual "Flower-Show Match" which brings memories of my own childhood floating to the surface.

Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man, pg. 48

I loved the early morning; it was luxurious to lie there, half-awake, and half-aware that there was a pleasantly eventful day in front of me…. Presently I would get up and lean on the window-ledge to see what was happening in the outside world…. There was a starling's nest under the window where the jasmine grew thickest, and all of a sudden I heard one of the birds dart away with a soft flurry of wings. Hearing it go, I imagined how it would fly boldly across the garden: soon I was up and staring at the treetops which loomed motionless against the flushed and brightening sky.

Slipping into some clothes I opened my door very quietly and tiptoed along the passage and down the stairs. There was no sound except the first chirping of the sparrows in the ivy. I felt as if I had changed since the Easter holidays. The drawing-room creaked as I went softly in and crept across the beeswaxed parquet floor. Last night's half-consumed candles and the cats half-empty bowl of milk under the gate-legged table seemed to belong neither here nor there, and my own silent face looked queerly at me out of the mirror. And there was the familiar photograph of "Love and Death", by Watts, with its secret meaning which I could never quite formulate in a thought, though it often touched me with a vague emotion of pathos.

When I unlocked the door into the garden the early morning air met me with its cooled purity; on the stone steps were the bowls of roses and delphiniums and sweet peas which Aunt Evelyn had carried out there before she went to bed; the scarlet disc of the sun had climbed an inch above the hills. Thrushes and blackbirds hopped and pecked busily on the dew-soaked lawn, and a pigeon was cooing monotonously from the belt of woodland which sloped from the garden towards the Weald. Down there in the belt of river-mist a goods train whistled as it puffed steadily away from the station with a distinctly heard clanking of buffets. How little I knew of the enormous world beyond that valley and those low green hills.

by

Siegfried Sassoon

The Old Century

and seven more years

In his sixth book, The Old Century and seven more years, Siegfried writes (now as himself) of his childhood in a country house in Kent and his experiences at Cambridge University. Siegfried, like myself, suffered from illness as a child and his descriptions of the days when the warmer weather began, to my invalid ears, is a descriptive paradise.

The Old Century and seven more years, pg. 52

When the warmers weather began, a little tent was put up for me on the lawn. Every morning I was carried downstairs on a stretcher to spend the day in my tent.

To be out of doors again at that time of year was indeed like coming back to life. But it was more than that, for the illness had made my perceptions detached and sensitive. I know how memories idealises things; but I think, all the same, that this was my first conscious experiences of exquisite enjoyment. The Tent gave me a feeling of independence and security as I lay there and listened to a pattering shower or gazed at the wisps and shoals of silvery cloud on mornings when the air was heavenly fresh and even the sky looked innocent - mornings when I was alone and the dew not yet off the grass in the undiminished shadows of that garden world.

by

Siegfried Sassoon

I was lucky enough to pick up the first edition of this book in Hay-on-Wye, coincidently an important location from my own childhood for it's yearly book festival, where I spent the majority of it following around Stephen Fry as he went about his business. He was very polite about it.

Comments