The Lost Exhibitions of London

- Lilium

- Mar 10, 2021

- 7 min read

In this article we explore the lost exhibitions of London, the Great Exhibition held at the Crystal Palace in 1851, the Franco-British Exhibition held in 1908, the exhibitions produced by Imre Kiralfy and the Japan-British Exhibition.

The Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations or The Great Exhibition (sometimes referred to as the Crystal Palace Exhibition in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition that took place in Hyde Park, London, from 1 May to 15 October 1851. It was the first in a series of World's Fairs, exhibitions of culture and industry that became popular in the 19th century.

The Great Exhibition was organised by Prince Albert, Henry Cole and other members of the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce as a celebration of modern industrial technology and design.

Famous people of the time attended, including Charles Darwin, Karl Marx, Michael Faraday, Samuel Colt, members of the Orléanist Royal Family and the writers Charlotte Brontë, Charles Dickens, Lewis Carroll, George Eliot, Alfred Tennyson and William Makepeace Thackeray.

A special building, nicknamed The Crystal Palace, or "The Great Shalimar", was built to house the show. It was designed by Joseph Paxton with support from structural engineer Charles Fox, and went from its organisation to the grand opening in just nine months. The building was architecturally adventurous, drawing on Paxton's experience designing greenhouses for the sixth Duke of Devonshire. It took the form of a massive glass house, 1848 feet long by 454 feet wide (about 563 metres by 138 metres) and was constructed from cast iron-frame components and glass made almost exclusively in Birmingham and Smethwick.

From the interior, the building's large size was emphasized with trees and statues; this served, not only to add beauty to the spectacle, but also to demonstrate man's triumph over nature. The Crystal Palace was an enormous success, considered an architectural marvel, but also an engineering triumph that showed the importance of the Exhibition itself.

The official descriptive and illustrated catalogue of the event lists exhibitors not only from throughout Britain but also from its 'Colonies and Dependencies' and 44 'Foreign States' in Europe and the Americas. Numbering 13,000 in total, some of the exhibits included:

The Koh-i-Noor, meaning the "Mountain of Light", the world's largest known diamond in 1851, was one of the most popular attractions of the India exhibit and was acquired in 1850 as part of the Lahore Treaty.

The Daria-i-Noor, one of the rarest pale pink diamonds in the world, was shown.

The early 8th-century Tara Brooch, discovered only in 1850, the finest Irish penannular brooch, was exhibited by the Dublin jeweller George Waterhouse along with a display of his fashionable Celtic Revival jewellery.

Mathew Brady was awarded a medal for his daguerreotypes, which became the first publicly available photographic process.

"The Trophy Telescope", so called because it was considered the "trophy" of the exhibition, was shown.

Six million people—equivalent to a third of the entire population of Britain at the time—visited the Great Exhibition. The average daily attendance was 42,831 with a peak attendance of 109,915 on 7 October.The event made a surplus of £186,000 (£26,137,440 in 2021), which was used to found the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Science Museum and the Natural History Museum. They were all built in the area to the south of the exhibition, nicknamed Albertopolis, alongside the Imperial Institute. The remaining surplus was used to set up an educational trust to provide grants and scholarships for industrial research; it continues to do so today.

The building was later moved and re-erected in 1854 in enlarged form at Sydenham Hill in south London, an area that was renamed Crystal Palace. It was destroyed by fire on 30 November 1936.

You can take a virtual 360 tour that lets you wander around the Hyde Park’s Crystal Palace below. Using a combination of CGI and 360 photography which overlays the historic building onto the present-day site, visitors can switch between then and now.

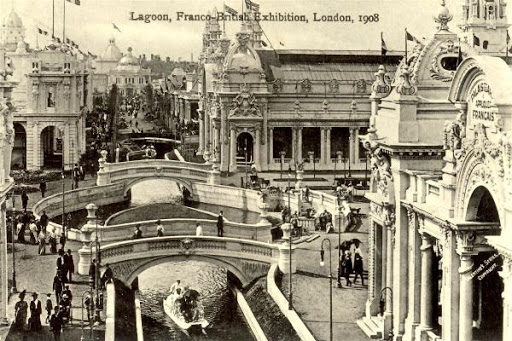

The Franco-British Exhibition

The Franco-British Exhibition of Science, Arts and Industry was a large public fair held in London between 14 May and 31 October 1908. The fair was the largest exhibition of its kind in Britain, and the first international exhibition co-organised and sponsored by two countries. It covered an area of some 140 acres, including an artificial lake, surrounded by an immense network of white buildings in elaborate (often Oriental) styles.

Imre Kiralfy, a famous exhibition organiser in his time, was a key figure in the craze for public exhibitions in the early 20th century. As Commissioner-General for the Franco-British Exhibition, he developed the exhibition grounds on farmland on 140 acres at Shepherd’s Bush where he built the Great White City and Stadium. The stadium was a last-minute addition when London took over hosting the 1908 Olympics.

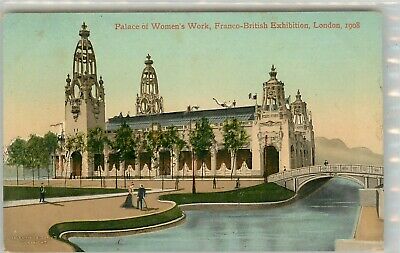

The White City was named for the white plaster finish of its building exteriors in “wedding-cake style” but despite the overall whiteness of the fair, the two organising countries of the first exhibition held there, that of 1908, had different architectural styles. There were some 120 exhibition buildings and 20 pavilions, most designed in an Oriental style, with domes and arabesque arches. They were linked by a network of roads, bridges, and waterways, and centred around an artificial lake.

The halls included French and British Palaces of Industry, a French Artisan’s Palace, the prominently-placed Palace of Women’s Work (celebrating famous figures from Elizabeth I to Florence Nightingale), a Fine Art Palace (with paintings by Hogarth, Gainsborough, Corot, Courbet), huge Machinery Halls and more.

In the Garden of Progress, the Pavilion of the City of Paris was said to give one “the reposeful pleasure always attending the contemplation of a pure work of art.” A number of model villages were reconstructed to celebrate imperial achievements, such as Ballymaclinton, a “genuine” Irish village, and a French Senegalese village, with live attractions. There were also cafés, restaurants and funfair rides.

Meant initially as a trade fair, it was also undeniably a fun fair, with a lot of music all around and several exciting attractions, notably the famous flip flap. The exhibition, the largest of its kind in Britain, attracted some 8.5 million visitors from all over Britain and France. It was even a financial success with receipts of over £420,000 (£50,857,682 in 2021).

Imre Kiralfy had produced other exhibitions in the old century. He produced Venice in London, a spectacular held at Olympia from 26 December 1891 to January 1893. The year after Kiralfy created an exhibition on the twenty-four acre Earl's Court Exhibition Centre grounds which he rebuilt in a Mughal Indian style. The Empire of India Exhibition opened the site in 1895, and was the first of a series of annual exhibitions there including the Victorian Era Exhibition in 1897, the International Universal Exhibition in 1898 and the Greater Britain Exhibition in 1899. The catalogues of the exhibitions can be read here.

Japan-British Exhibition

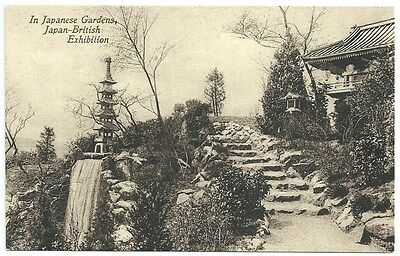

In 1910 the White City was used again for the Japan-British Exhibition. It was the largest international exposition that the Empire of Japan had ever participated in and was driven by a desire of Japan to develop a more favorable public image in Britain and Europe following the renewal of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance. It was also hoped that the display of manufactured products would lead to increased Japanese trade with Britain.

The Japanese display covered 242,700 square feet, three times the space Japan occupied at the previous Paris Exhibition of 1900, not including an additional 222,877 square feet for two large Japanese gardens.

The Japanese gardens had to be constructed from scratch at the Exhibition site. Since authenticity was regarded as of the utmost importance, trees, shrubs, wooden buildings, bridges, and even stones were brought in from Japan.

One of the many aims of the Exhibition was to introduce the civilization of Japan to the western world, showing past, recent present and projected future. The intent was to show that Japan was not a country that had suddenly leapt from a state of semi-barbarism to one of high civilization in the middle of the nineteenth century, but had always been “progressive”, and that the modernization of Japan since 1868 was only a natural progression. This was illustrated with twelve impressively full-sized dioramas with wax figures, showing the progression of Japanese history.

Each of the Japanese government ministries was represented, along with the Japanese Red Cross and the post office, showing displays of the modern systems and facilities used by the governmental departments.

Almost 500 Japanese firms sent items to London. Care was taken only to display the highest possible quality, to offset popular images that Japanese products were cheaply made and tawdry. Artists represented included ceramicists Yabu Meizan and Miyagawa Kozan as well as the cloisonné artists Namikawa Sōsuke, Kawade Shibatarō and Ando Jubei.

Lacquer artist Tsujimura Shoka won a gold medal for a box decorated in hiramaki-e with a stylised depiction of an asunaro plant. The Samurai Shokai Company won a gold medal for a set of metalwork pieces.

In addition to manufactured goods, traditional and modern fine arts, and arts and crafts were well represented, including nihonga (Japanese-style) and yōga (Western-style) painting, sculpture, lacquerwares, and woodcuts. One of the most popular craftsmen in the Exhibition was Horikawa Kozan, a celebrated potter. He was invited to demonstrate pottery-making and repair priceless antiquities, some of which had been in the possession of British collectors for generations.

A visit by Queen Alexandra in mid-March, in advance of the opening, added publicity and royal prestige to the Exhibition. The death of King Edward VII caused the opening to be delayed until 14 May. By the time the event closed on 29 October, over 8 million visitors had attended.

The final stage of the Exhibition was the disposal of the exhibits. These fell into three categories: those to be sent back to Japan (400 boxes in three separate shipments), those to be presented to various institutions (over 200 boxes divided between thirty recipients), and those to be sent to other cities in Europe where international exhibitions were projected for the near future (Dresden and Turin, both in 1911). The Chokushimon (Gateway of the Imperial Messenger) (four-fifths replica of the Karamon of Nishi Hongan-ji in Kyoto) was moved to Kew Gardens a year later, where it still can be seen today.

Reading Recommendations & Content Considerations

Catalogue 1891-92

Comments